Be The People: Seeing America Through Jon Cherry’s Lens

Belle Townsend on Jon Cherry’s photographic exhibition at Centre College’s Norton Center for the Arts

Photo by Jon Cherry

Having never been to Centre College’s Norton Center for the Arts, I entered unsure of where I was going. I followed the most obvious path forward until the lighting shifted and photographs began lining the walls. The space opened itself to me before I even realized I’d arrived. There was something fitting about that: the exhibit not waiting behind a guarded door, but meeting viewers almost immediately, the way the country meets us everywhere we go whether we’re prepared for it or not.

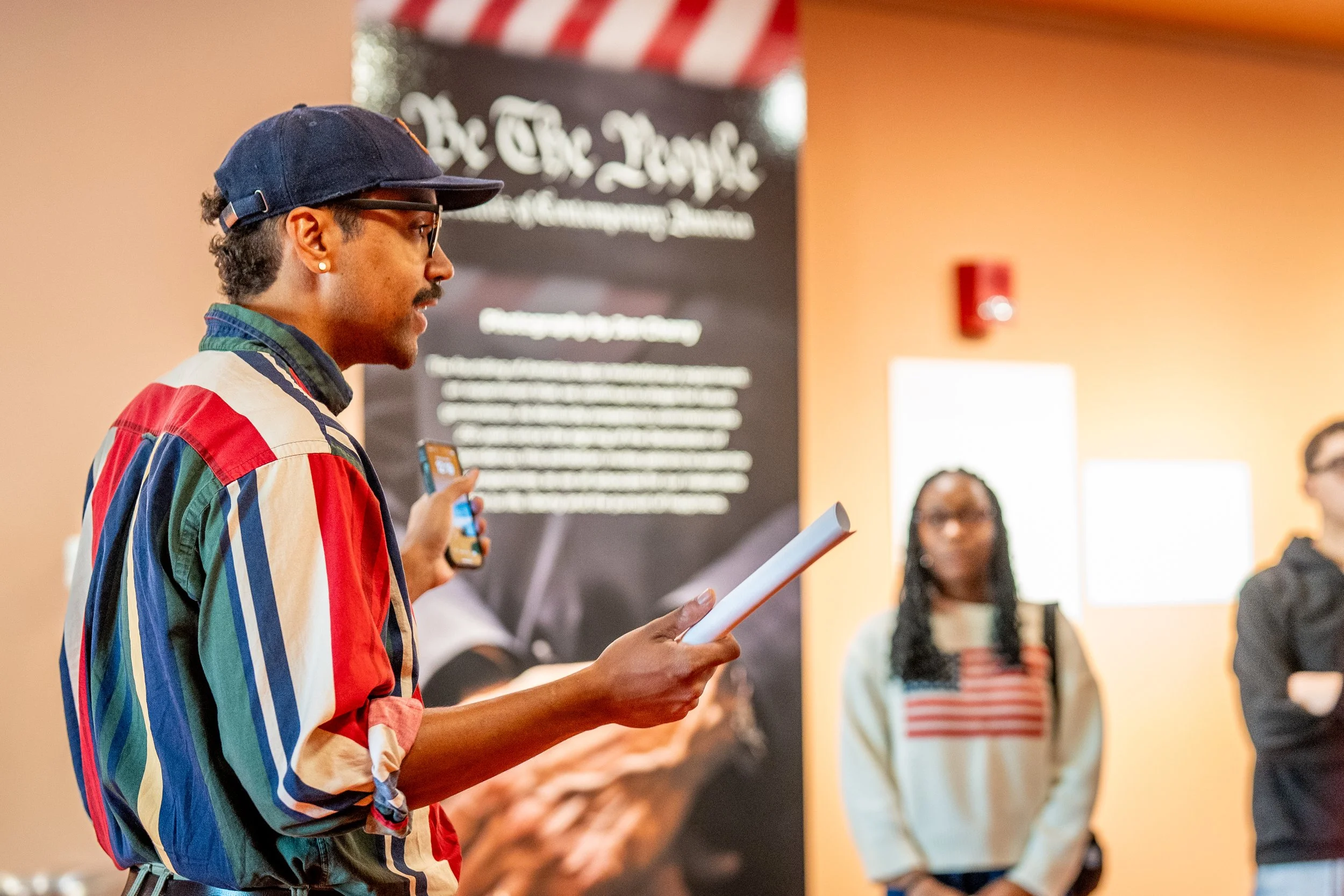

Photo courtesy of Jon Cherry, reception of Be The People

Jon Cherry’s Be The People: Portraits of Contemporary America spans five years of his work—years dense with upheaval, contradiction, and civic strain. The exhibition arrives in a moment when Kentucky, like the rest of the nation, is negotiating what it means to live together under a shared flag while carrying vastly different histories, fears, and convictions. The Norton Center organized the show partly in response to concerns from conservative students who felt unheard on campus, inviting Cherry to create something that could hold many Americas at once.

The artist statement sets the tone: layered, introspective, and unflinchingly honest about the complexity of identity in this country.

“I consider myself deeply American,” Cherry writes. “I am Black, white, and Indigenous. I am a child of both the chattel and the possessor, the oppressed and the oppressor.”

Born on the nation’s largest military base to two veterans, raised in the South, Cherry carries a sense of inheritance—one that refuses to flatten the American story into an electoral map or an inevitable conclusion. He acknowledges survival and contradiction as central to his understanding of home.

Cherry’s journey as a photographer began with urgency: standing in downtown Louisville in 2020 as protests erupted after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Without formal training in journalism or art, he followed instinct. He describes a “desperate search to contribute to what seemed unchangeable.” That feeling threads through the exhibition: the desire to witness, to understand, to ask questions even when answers remain elusive.

Photo by Jon Cherry

Cherry’s openness—to strangers, to chaos, to the emotional truth inside any given moment—is the heart of his approach. He resists the traditional notion of objectivity in journalism, calling impartiality, “a great goal the way perfect pitch is a great goal—worth striving for, not necessarily possible.” What matters to him is the awareness of one’s own biases, not the pretense of having none.

“I’m not trying to develop conclusions,” he told me. “I want people to ask questions.”

Photo by Jon Cherry

His work accomplishes exactly that. Moving from photograph to photograph feels less like viewing a series than like turning the pages of a national autobiography—one written in moments of tension, endurance, and unresolved contradiction. A young man in a MAGA hat raises his arms at the People’s March ahead of Trump’s 2025 inauguration. Members of the Black militia, NFAC, march near Churchill Downs, demanding justice for Breonna Taylor. Cadets choke on tear gas during CBRN training; Afghan refugees stand in line at Fort Pickett, waiting. Tornado survivors in Indiana and Kentucky face the remnants of their homes. On Christmas Eve, Kentuckians haul toys on a couch strapped to a trailer through a devastated neighborhood. Paramedics tend to COVID patients in their bedrooms during the Delta surge.

Taken together, the images resist hierarchy. No single photograph claims to explain the country. Instead, they insist on proximity—placing grief beside ritual, politics beside survival, spectacle beside care—and asking the viewer to hold them all at once.

Photo courtesy of Jon Cherry, reception of Be The People

These images trace the emotional and civic whiplash of the last half decade, a stretch of time that has felt both unreal and unrelenting. So much devastation and so much pushback, spiraling through protests, pandemics, natural disasters, political ruptures. Cherry’s photographs catch each of these moments mid-breath, stitching together a timeline that many of us lived through without ever fully taking it in.

These images reveal the simultaneity of the American experience. Its grief and pride, its fear and resilience, its competing stories of patriotism and belonging. Cherry’s curation doesn’t tell viewers what to believe. Instead, it places them inside the storm of the last five years and asks them to sit with the tension.

That tension is woven into the exhibition’s structure, too. Because the Norton Center wanted the show to be accessible to minors and understood across the political spectrum, Cherry and the curatorial team made careful choices about which images to include. A few photographs featuring profanity or highly charged language didn’t make the final cut, not out of avoidance but out of a desire to meet the expectations of the space. Cherry told me that shaping the exhibition under these considerations required a different kind of impartiality than photographing in the field.

“Impartiality in the field is one thing,” he said. “Curating for a space that needs to appear impartial is another.”

Reflection stations throughout the gallery invite visitors to respond to questions of freedom, justice, belonging, and liberty. In one notebook, two strangers had written to each other days apart. The exchange embodied the exhibition’s aim—civic thought rather than partisan reaction, and a public square grounded in curiosity instead of faction.

Cherry is deeply aware of the history of extractive photography in rural and marginalized communities. Appalachia especially, he said, has been “a farm for poverty photos for 100 years.” He refuses to replicate that harm. He sees his subjects not as symbols or material for outsider consumption but as people whose consent, dignity, and humanity matter more than any image.

Photo courtesy of Jon Cherry, reception of Be The People

“It’s rare in life to have a stranger show up and want to know everything about you,” Cherry said. “That curiosity opens people.”

That belief shapes how he works. Cherry often returns to the people he photographs—staying with them, checking on them, learning their stories beyond the frame. He breaks the traditional journalistic rule of distance on purpose. His photographs carry a deep gratitude for those who allow themselves to be seen, particularly the people featured in this exhibition. Their vulnerability is not taken for granted but treated as an offering, one he is intent on honoring.

“I get too close to every story,” he told me. “I’m a human being first, journalist second.”

Walking through the exhibition, that humanity is everywhere, not as abstraction but as presence. It appears in the posed portrait of a young boy standing near the wreckage of his home; in the strain on a paramedic’s face as he kneels beside a patient; in a young Afghan child staring out from a military recreation center, a world away from Kabul. And it appears, more uneasily, in the hands gripping the American flag as protesters raise it on the western steps of the Capitol on January 6.

Photo by Jon Cherry

Be The People isn’t a strict chronology or a political argument. It is, as Cherry describes it, a meditation on the last five years—a reflection on a period that is still unfolding. Some of the images already feel historical; others feel like warnings.

Cherry is not hopeful about political institutions, he admitted, but he does believe in ordinary people. The title itself reframes who holds power in this country. Not the politicians in the photographs, not the systems they represent, but the people who stand in front of Cherry’s lens—celebrating, grieving, resisting, surviving.

Photo courtesy of Jon Cherry, reception of Be The People

“Everyone who visits the exhibition is governed,” he said. “The exhibition centers the common people who shape this country.”

After finishing my walk through the gallery, I stepped into the nearby restroom. When I came back out, I found myself drawn once more toward the exhibition space. Seen again, it felt less like a destination than a threshold—a place you pass through rather than arrive at. The question at the heart of the show, What does it mean to be an American?, no longer felt contained by the gallery walls but carried outward, following visitors as they moved back into the world.

Cherry doesn’t answer the question. He never intended to. Instead, he insists on the importance of asking it again and again, especially in a country where origin stories collide and inheritances run deep. “I hope these images offer a moment of pause,” he wrote. “A chance to consider another perspective or to enhance one’s own.”

If the purpose of art is to sharpen our attention, then Be The People succeeds not by resolving contradiction but by illuminating it. The exhibition insists on dignity in observation, honors the people who allowed Cherry into their lives, and invites viewers to look more closely—at the country, at one another, and ultimately at themselves.

Be The People is on view now at Centre College’s Norton Center for the Arts.