Shall I Compare Thee

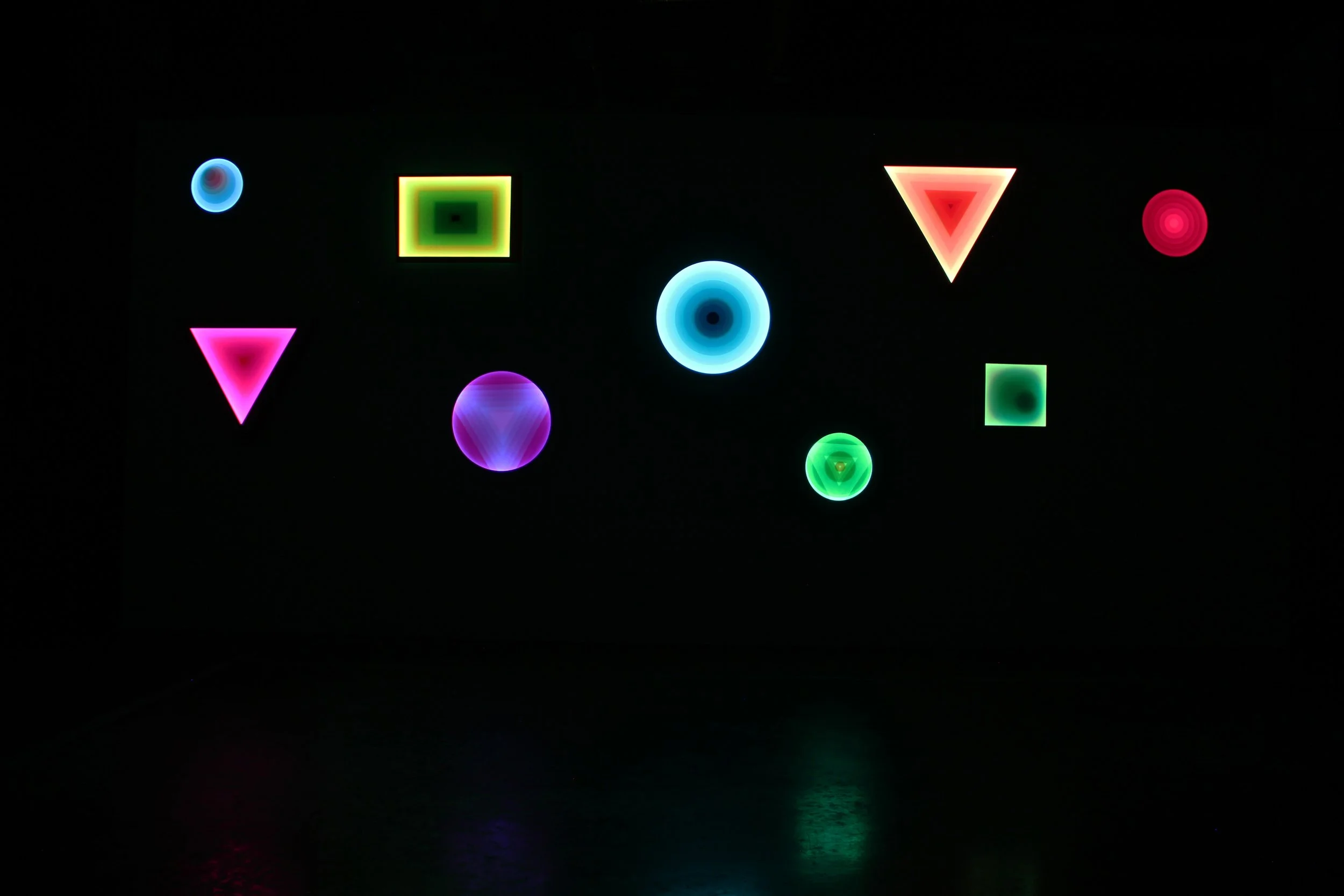

Letitia Quesenberry, phosphenes at Quonset Hut

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date

- Shakespeare's Sonnet 18

When the speaker of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 addresses the young man, he seizes upon the writer’s plight—using comparison. Words cannot express, language cannot approach the lover’s passionate feelings for the beloved. The speaker takes on the sonnet’s traditional subject matter—the passage of time—with metaphors of seasons and flowers.

Bringing it down home, one of the reasons I love Kentucky is that Southerners revel in poetic language. We employ colorful figures of speech: slicker than snot, rougher than a cob, like a hair on a biscuit. These similes create sensory images that give distinct textures and shapes in the imagination. They stick in your craw.

The work of Letitia Quesenberry is described best through vivid comparison.

Having known Letitia for twenty-five years as a friend and curator, and having witnessed the morphing of many bodies of work, I find it difficult to maintain a critical distance. I must reach toward familiar genres of art such as minimalism and perceptual art to seek similarities and resonances. What is Letitia’s art like? What does it resemble? How can the audience find descriptive verbiage to grasp? Like her peer Tara Jane O’Neil, Quesenberry experiments and improvises and often evades definition.

The group of artists who first jump to my mind originate in the California Light & Space movement (a form of West Coast minimalism that flourished during the 1960s and 70s). Artists, like Larry Bell, incorporate technology and are concerned with how art can alter perception and express the transience of experience. The practitioners work in resin and glass and other translucent, unconventional materials. They ask how seeing corroborates or obscures memory.

I also think of Dan Graham—who builds mirrored glass pavilions, sculptures that trick the viewer’s sense of space and self. This work defies easy description because it changes according to the time of day, the atmospheric condition, and the position of the audience. The artist’s materials deflect interpretation and embrace their own opacity and slipperiness.

A correspondence with Brazilian Neo-Concrete or Constructivist art occurs to me. Artists like Helio Oiticica and Lygia Clark (who came into prominence during the 1960s) play with shifting geometric forms and visual awareness. Their sculptural interventions challenge the spectator’s perception and invite psychic interaction. Clark and Oiticica expect viewers to experience their sculptures in time and space. Their form of abstract and interactive art feels poetic and intuitive. It remains changeable, hard to pin down. It invites sensation, participation.

What is Quesenberry’s art about? Why ask the question. The light boxes, the pulsing circles, and the vivid Polaroid forms offer moments of radiance and resonance. Quesenberry’s luminous constructions are meant to be felt, to be experienced. They may cause a visual shift, or offer a glimpse of memory.

On a summer’s day during the opening reception, the light over Phoenix Hill passed into dark. Together at the Quonset Hut, we traversed the long days of the solstice and felt the transience, the passing of time—with the enchantment of Tara Jane O’Neil’s music and within the embrace of a multitude of friends.

This article was written by Leslie Millar, the curator of phosphenes. Leslie is the President of the Kudzu jelly Board of Directors as of the publishing date of this article. She was not financially compensated for this piece.