A Hillbilly Elegy to Climate Collapse

Ceirra Evans’ Come Rain or Shine at Institute 193

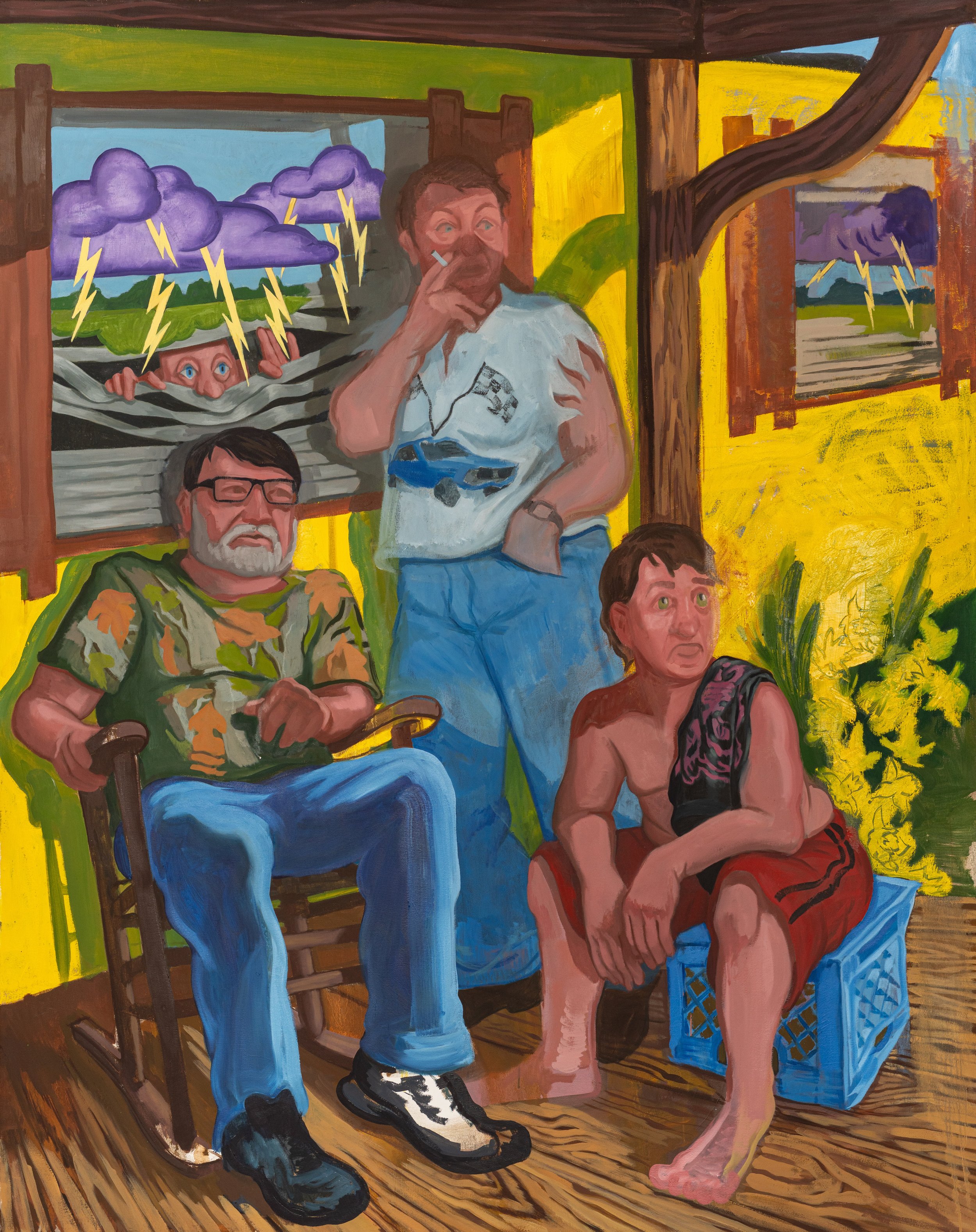

Ceirra Evans, Fixin’ to rain, 2025, Oil on canvas, 54” x 68”

Come Rain or Shine, Ceirra Evans’ show at Institute 193, runs in circles—like a dog chasing its tail—around the stereotypes of Appalachian life. The paintings are set against a tumultuous backdrop of social, political, and climate catastrophe. Yet, in the face of global meltdown, Evans holds fast to the urgency of friendship, frugality, and solidarity.

These remarkable paintings touch a deeply tragic vein: the anti-heroic, working class, and humbly gladiatorial. In their oily ambiguity, Evans paints rural life as a kind of everyday cosmological circus maximus, where even the smallest gestures feel worthy of a mythic frieze. But instead of conquest and carnage, the tableaux depict care and closeness, no matter how clumsy or small, as the highest form of heroism.

If I were to chance encapsulating this series of paintings into a single hyphenated ism, it would unapologetically be: Feminist–Redneck–American–Magical–Realism. But these works defy simple categorization. They stretch beyond any -ism in their wavy, cloud-like density and plastic intensity. At first glance, the content appears to center on the vernacular—upon closer inspection, they entangle small tales with care-filled moments of repose and humility in the face of extraordinary circumstances.

Ceirra Evans, Any Good News?, 2025. Oil on canvas, 46” x 56”

Any Good News? stands out as Evans’ American Gothic. Instead of the aged and ambiguously iconized New Deal-era farmer and wife of the midwest, the audience is met by two androgynous and scrappy figures who streak across the picture plane in an undulating splash of blinding afternoon light. The characters share a fleeting moment of kindness. An off-grid, unofficial, word-of-mouth transmission forms within the very real and increasingly necessary horizontal network of mutual aid, and represents a survival tactic so often employed by rural and especially queer rural folk.

Like comic strips or holy tableaux, the faces in these mise-en-scènes resemble sun-struck heroes–squinting, grimacing, grinding their teeth as they perform their vigilant office. Most of Evans’ figures aren’t suspended in grand gestures, but in quiet, everyday acts that carry mythic weight. As in Fixin’ to rain and Milk eggs and bread, these scenes walk the line between tragedy and comedy, and still remain rooted squarely—and bluntly—in the mundane. In that very everydayness, they offer a voluptuous, savory, and sometimes playful buffet of brushstrokes and drips. The paintings conjure quiet repose and meditate on the fragile house of cards that is–or once was–the American dream.

Ceirra Evans, In Spite of Ourselves, 2025. Oil on canvas, 66” x 42”

In the daydream clouds of In Spite of Ourselves, the viewer witnesses humanity approaching its ultimate quagmire. Big Momma Nature, through her accelerating cycles of extreme weather, begins to grab a fossil-fueled bull by the horns. She’s here to regulate the insane patriarchal pelvic thrust we’ve come to call “modern civilization.”

Evans’ characters don’t live at the center of an empire. They’re on the other end of the charioteer’s whip–outside the financial cores of disaster capitalism. They persist in the hollers, now flattened, water-logged, or on sun-bleached mountains, outside of the shadowy smokestacks of so-called civilization.

And the cherry on top of this once ice-creamy, air-conditioned dream? “All that is solid melts into air.” In Evans’ paintings, the material world dissolves–along with our very perception of reality itself. Heat waves bend every act of human survival into an undulating, baroque swirl of perspiration and spiritual exhaustion—that feels not quite nightmarish, but deeply tender and strange.

The sacred can appear in the act of watching a storm roll in. Turn away and you risk being swept away. But if you face the dark clouds, you just might dodge the storm’s equalizing hammer. This pendulum swing—between wonder, cosmic attunement and a clownish, desperate, and deeply necessary struggle to survive—lies at the heart of the tragicomedy within Come Rain or Shine.

Even as the storm swells, it might be eclipsed by love, joy, and deep listening. This kind of watching—gazing at the sky that once signaled pastoral calm but now suggests potential extinction— becomes synesthetic and deeply resonant. This sky, a sky that strikes down upon creation with ever-increasing frequency and fury, awakens senses once dulled by technology. As Mother Nature begins to regulate humanity, death draws closer. And we, in turn, draw closer to each other and to the earth. We start to listen: to suffering, to kin, to the need for solidarity, and subtler necessities.

Ceirra Evans, Kentucky Meat Shower, 2025. Oil on canvas, 36” x 36”

In the sunburnt, shadowy density of Kentucky Meat Shower—where turkey vultures melt like sub-tropical flamingos with tummy aches—Evans offers magic-hour warmth that casts a heat-lamp on local myth. During climate collapse, this magic hour becomes ever-expanding, stretching across entire days in “stops and starts,” in an uncanny and unpredictable parody of what we used to call weather.

Evans captures how, as clouds resemble a cotton-candy sublime, an absurd need remains. In Gotta Do What You Gotta Do, blow-dried frostbitten roses form in an unseasonably cold snap and illustrate an extreme that has become all too normal. These paintings leave room for thinking and seeing the small wonders of rural survival in the face of near-insurmountable odds.

Evans’ work feels particularly urgent because it portrays rural life as deeply resilient and attuned to economies of care, despite mainstream media messaging to the contrary. These paintings invite subtle observation. A silent awe and respect for family, friends and the tenuousness of life itself on the edge of extinction and erasure. Sun-drenched porch-sitting. Old-fashioned daydreaming. Letter writing, garden tending, and slow talking. At the heart of each tableau: love in the face of mortality. As Belle Townsend puts it: “This exhibition is a document, a witness, a love letter, and a warning. If the storms are getting stronger, the stories we tell about each other have to be, too.”

Ceirra Evans, Gotta Do What You Gotta Do, 2025, Oil on canvas, 38” x 52”