Between Ruin and Renewal

All Four Seasons in Equal Measure at the Carnegie in Covington, KY

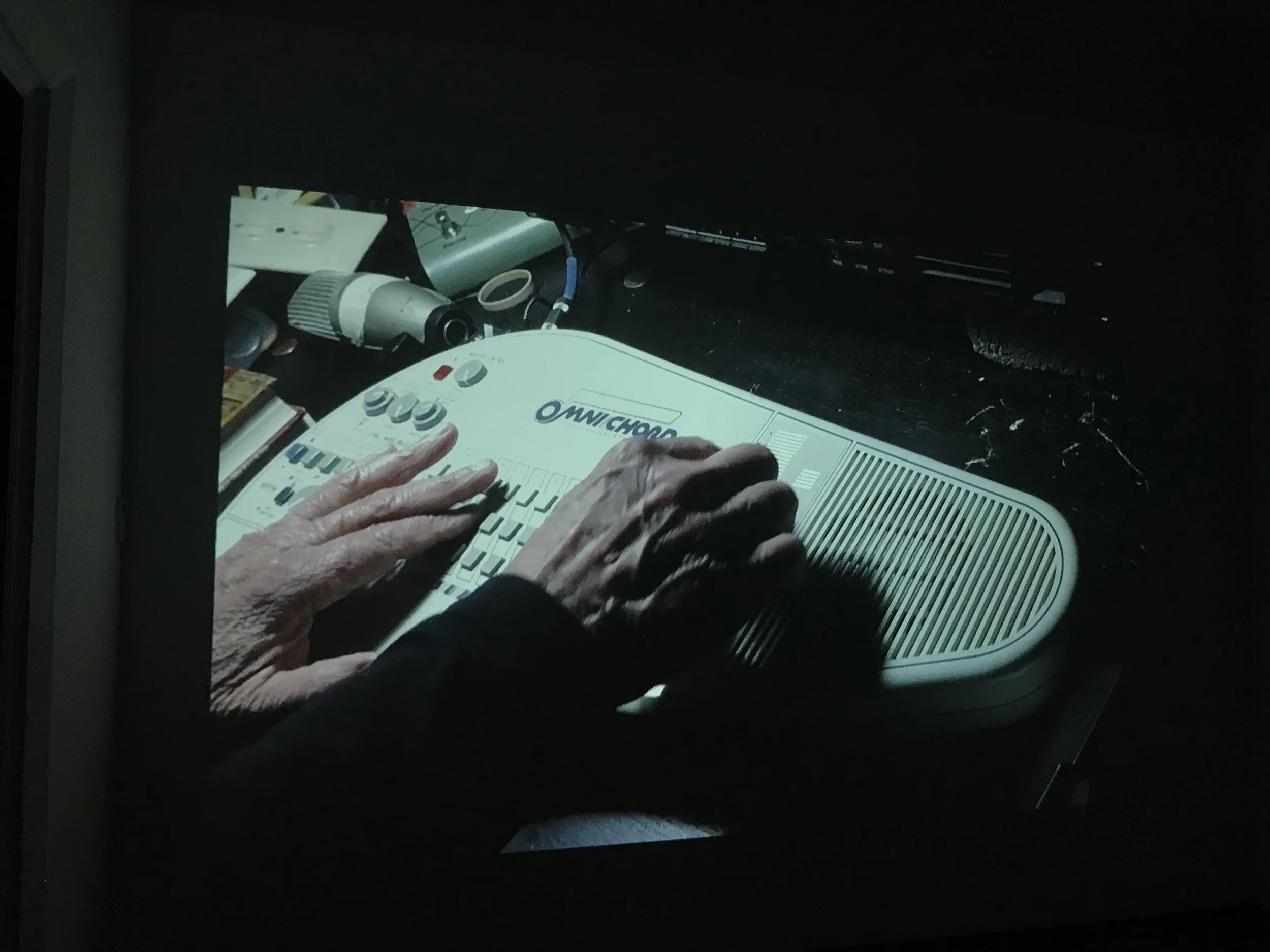

Still from a Documentary about the making of Twit

“What is a course of history or philosophy, or poetry, no matter how well selected, or the best society, or the most admirable routine of life, compared with the discipline of looking always at what is to be seen? Will you be a reader, a student merely, or a seer? Read your fate, see what is before you, and walk on into futurity.”

“If we seek a title for this new epoch, one that emphasizes our species’ responsibility in the creation of this catastrophic set of affairs, while holding open the possibility—indeed the necessity—of an ethical turn, then instead of relying upon the term anthropos, why not draw upon the etymology of the word human… The term human (derived from the Latin humanus) is cognate with the Latin word humus, which signifies the earth underfoot, the ground or soil, and hence is intimately bound to the term humility, the quality that holds us close to that earthly soil. Perhaps, then, a more appropriate title for the geological epoch now upon us would be the Humilocene—the Age of Humility.”

There is an air of loneliness and death about All Four Seasons in Equal Measure. Loosely inspired by Thoreau’s Walden—his philosophical meditation on solitude and self-reliance beside a pond in rural Massachusetts—the exhibition glances toward the growing “edge effect” between ecological concern and contemporary art. Thoreau was writing in 1845, as the Industrial Revolution’s tendrils reached deep into the colonial West. Industrialization’s impact was understood at that time primarily in terms of dirty air, poor sanitation, and the displacing noise of capitalist expansion—afflictions one could still escape by moving a few kilometers upstream.

Fast forward 180 years: solitude, at least the kind Thoreau sought, has become nearly impossible. We now inhabit a fully terraformed world, a geological epoch often called the Anthropocene. Unless one vigilantly seeks an off-grid life, the contemporary condition is defined by hyperconnectivity, endless mediation, and pollution of all kinds. As David Abram writes in Becoming Animal, we live enclosed within a purely human world, increasingly unable to read, interpret, or even see the “more-than-human worlds” of other species.

In this moment of climate catastrophe, All Four Seasons in Equal Measure reads as both lament and plea: mourning the loss of biodiversity and climatic predictability while urging us to look and listen to what remains of the wild. Even a small acre of trees—like the one surrounding the house where curator Monique Long stayed during their Great Meadows Foundation residency—now offers rare reprieve in a world on fire.

Shohei Katayama, Relics from the Country of Eternal Light. Photo by Jesse Ly.

Yet in an exhibition inspired by nature, there seems to be so little of it present. Most works reveal only traces of life: representations of trees, plants, a few animals and birds, a dragonfly exoskeleton in a vitrine, collected forest debris encased in glass, and the decaying remains of Arctic fauna in tiny test tubes. This scarcity evokes biologist E.O. Wilson’s term for our epoch, the Eremozoic—“the age of loneliness.” As ecosystems collapse and human populations expand, other species recede into ever smaller edge habitats, their presence fading toward enclosure, collapse, and extinction.

Thoreau’s solitude, by contrast, was filled with sensual attunement to other beings. Today, what remains of that fecundity is polluted and largely absent from human experience; even the wild that survives is laced with forever chemicals, microplastics, and heavy metals.

Kiah Celeste, The Little Virgin that Could. Photo by Jesse Ly.

Still, the works in the exhibition embody deep ecological concern and attentiveness to loss—most notably those by Rachel Singel and Kiah Celeste. Singel’s intaglio prints of woodland creatures, printed on paper made from harvested invasive plants, serve as quiet memento mori for ecosystems on the brink. Celeste’s sculpture, like much of her oeuvre, is composed entirely of found and upcycled materials—even the pedestal itself, as Monique Long notes, was built from salvaged components the artist sourced herself.

Then there is the mirror.

The oculus.

The rotunda.

The eye that sees.

An aperture for the human problem of cages, boxes, and vitrines.

Beyond blue and red, we’re of the same feather.

The works by Roy Taylor, Gibbs Rounsaval, and Britany Baker, and Shohei Katayama seem to loosely engage the architectural motif of the rotunda—an analog for the reflective opening of Walden Pond.

Wall text from the exhibition

Roy Taylor (aka paperworkfilms) takes an anthropomorphic and poetic look at birds in his short film twit. The piece playfully addresses our excruciating moment of tribalism and fascism, both global and domestic. Birds appear differently under varying light: blue on the left, red on the right. Yet as a magical aura emerges between them, offered by an oculus above, their wings shimmer together in a shared ultraviolet field where difference dissolves. Escaping their self-imposed Plato’s cave, they flock in harmony—a poignant metaphor for our polarized era.

Gibbs Rounsaval and Britany Baker’s meticulously rendered roundels, paintings, and drawings offer a departure from any hard-edged abstraction. These drawings are soft, attuned to light and pattern, especially Rounsaval’s, which seem near-photorealistic in their delicacy. For both, abstraction remains, especially up close, solidity dissolves into countless marks and textures. These works, like the endless complexity of a dappled canopy or forest floor, draw you in for a closer look, to inspect granules of graphite, pigment, or charcoal; echoing the fragile molecular cohesion of matter itself.

Housed within the Carnegie’s rotunda, the exhibition finds its cosmological axis in Shohei Katayama’s kinetic architectural intervention. His sculpture activates the oculus like a weather vane, mobile or sundial, linking sky and earth and drawing the eye to the amber stained-glass dome above. The spiraling structure creates continuity between floors, offering a dialogue between futurity, synthetic materiality, and the bourgeois social origins of Beaux-Arts symmetry.

Shohei Katayama, Earth Meets Sky. Photo by Jesse Ly.

There is something eerily augmented in the way Katayama’s work animates the space—as if a fragment of a digital steampunk world, like Final Fantasy VII, had materialized to infiltrate the architecture. Its exposed apparatus and armature suggest a kind of Fibonacci clock or whirligig without measurable time. Its spinning motion recalls an unnatural physics of suspension without beginning or end: a digital wheel of death from another dimension. This futuristic artifact, camouflaged in faux marble acrylic, hangs like a grim Holocene time traveler, carving itself into the cybernetic paradox between ruin and renewal.